Shemini Atzeres (also known as Simchas Torah) is a day of joy. But what is it, and what do we do on it? Let’s look at its roots.

Immediately when the Holiday of Sukkos ends, the Yom Tov of Shemini Atzeres begins.

“Shemini Atzeres” means “the eighth day, a [day of] restraint.” Shemini Atzeres gets its name from the Torah itself, which says,

The 15th of this seventh month shall be the festival of Sukkoth to God, [lasting] seven days. The first day shall be a sacred holiday when you may not do any mundane work. For seven days you shall present a fire offering to God. The eighth day is a sacred holiday to you, when you shall bring a fire offering to God. It is a time of restraint when you may do no mundane work.

– Leviticus 23:34-36

The actual term “Shemini Atzeres” is taken from another verse: “Day eight, a restraint it shall be for you, you shall do no mundane work” (Numbers 29:35). Of course, in English, that is better said as “The eighth day shall be a time of restraint for you when you shall do no mundane work.” But the Torah puts the two words together: “Shemini Atzeres,” and that is what we call the Holiday.

Why a “Restraint?”

So why does the Torah call it a “restraint?”

By “restraint,” the Torah basically means a day of calm, of no milachah (physically creative activity as defined by the Torah, but which I have translated as “mundane work”), a day of self-restraint. But the meaning goes deeper than that.

Here is an important point that can help us understand why the Torah calls Shemini Atzeres a “restraint.” Besides the other Laws of the Holiday, we also had to sacrifice special offerings at the Holy Temple on each Holiday, and each one has its special offering, different than those of any other Holiday. On each day of Sukkos we brought sacrifices on behalf of the well-being of all the other nations of the world. A total of seventy sacrifices were brought just for the Gentile nations, over the course of the seven days of Sukkos. On the first day we offer 13 bulls, on the second day 12 bulls, the third day 11 bulls, and so on, until the seventh day, when seventy bulls have been brought on the altar. However, on Shemini Atzeres, the eighth day, we bring just one

bull, and that is for the nation of Israel.

The Rabbis tell us:

Why is the Holiday called “atzeres,” a restraint? It is like a king who proclaimed a festival for seven days. He invited all his subjects to attend the feast for all seven days. When the seven days ended, and everyone was to leave, the king told his son, “Stay with me just one more day, and we will celebrate together, just you and I.”

Likewise, when Sukkos ends, Hashem says, “I have “restrained” you, that is, I have held you back another day, after Sukkos has ended. All Sukkos you have offered seventy Sacrificial Offerings at the Holy Temple on behalf of the nations of the world. Today, bring just one offering, and that will be for just you and Me. Together, we will celebrate, just you and I.”

– Rashi, Leviticus 23:36

Sukkos is a Holiday with several associations with the Gentile nations as well. But Shemini Atzeres is an additional day, an extra day during which the Jews celebrate their cherished relationship as the sons of Hashem.

In this way, Shemini Atzeres is different from the other Holidays. Sukkos, Passover, and

Shavuos, all celebrate miraculous events that Hashem did for us. Rosh Hashanah is the new year, during which Hashem “remembers” us (i.e., He judges us). Yom Kippur is the day we can be forgiven even our worst sins. Shemini Atzeres, however, celebrates our relationship with Hashem, and is not associated with any particular event.

Outside of Israel

Every Jewish Holiday except Yom Kippur has an extra day outside of the Land of Israel (though Rosh Hashanah has two days even in the Land of Israel). Therefore, any seven day Holiday, such as Passover, will actually have eight days when celebrated by people who live outside of Israel (even if they happen to temporarily be in Israel during that Holiday).

However, the extra day, the eight day for Sukkos falls out on Shemini Atzeres, which is a

Holiday of its own. Two Holidays are occurring on the same day! Therefore, we must assume some of the aspects of Sukkos, even as we observe the Holiday of Shemini Atzeres. So we eat in the Sukkah the night of Shemini Atzeres and the whole day of Shemini Atzeres. However, we do not make the Brachah (Blessing) that is normally made when eating in the Sukkah. Nor do we sleep in the Sukkah, nor do we use the Four Species during Shemini Atzeres.

Having said that, I must also add that many (particularly Chassidim) have the Custom not to eat in the Sukkah during Shemini Atzres. (Many great Rabbis have followed the Custom not to eat in the Sukkah during Shemini Atzeres, and we must respect that Custom with as great a reverence as we respect the Custom of those who eat in the Sukkah during Shemini Atzeres. If you have a doubt as to what to do, you should ask your Rabbi.)

Many who do not eat in the Sukkah during Shemini Atzeres have the Custom to say Kiddush in the Sukkah Shemini Atzeres during the day, and eat a little there (without saying the Brachah of “Sitting in the Sukkah,” of course). They then say a short prayer of farewell to the Mitzvah of sitting in the Sukkah, and they leave the Sukkah. The Holiday meal itself they eat in the house.

The second day of Shemini Atzeres, which is celebrated everywhere outside of Israel, is usually called Simchas Torah (Joy of the Torah), though in the prayers it is still called Shemini Atzeres.

One of the reasons we are so joyous on Shemini Atzeres is because during that Yom Tov we finish the yearly cycle of Weekly Torah Readings, and begin the cycle anew. We therefore rejoice and are very grateful for the Torah that Hashem has given us.

So on the first night of Shemini Atzeres, the second night, and the second day, it is the Custom to take all the Torah Scrolls out of the Ark and dance with them. Some people are given the honor to hold the Torah Scrolls and dance with them, and everyone else sings and dances in a circle or a line around them. This is done seven times, to represent the seven attributes with which Hashem manages and maintains the world (Chessed, Gevurah, etc., i.e., Kindness, Strength, etc.).

All the repentance and self-improvement we have been busy with for the past month and half culminates at this time. We begin with the declaration that Hashem is the G-d, and there is none other. We declare Hashem’s greatness. We ask Hashem to keep on helping us as we attempt to grow closer to Him. And then we rejoice over the Torah. And through that joy, we can merit a favorable judgment, because having joy for a Mitzvah has the power to annul a negative Heavenly decree.

Each and every Jew, no matter how great, and no matter how small he may think himself to be, is an equal inheritor to the Torah. The Torah says, “The Torah that Moses taught us is an inheritance to the Congregation of Jacob” (Deut. 33:4). We all have a right and a responsibility – like anyone who inherits a fortune — to the Torah. And we can all reap the benefits of that inheritance, if we avail ourselves of the Torah.

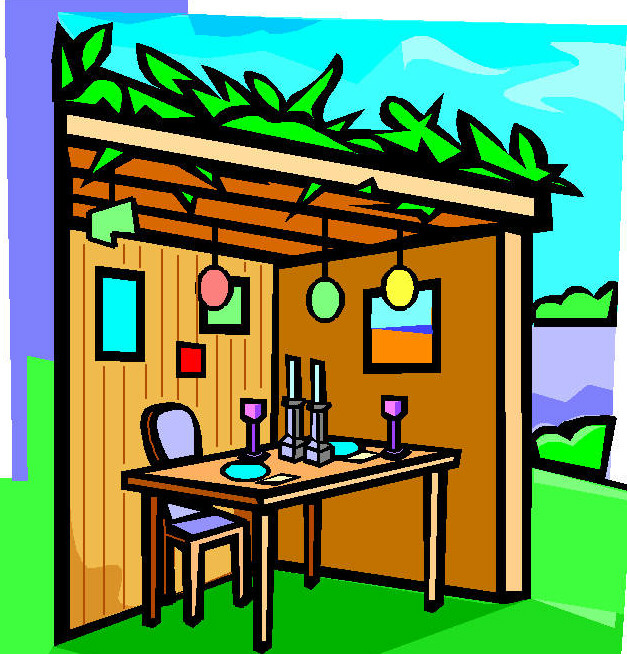

Here is a cutaway picture of a sukkah. Perhaps it gives you an idea of how a sukkah should look. Of course, a sukkah usually has four walls, or three walls built against the wall of a house.

Here is a cutaway picture of a sukkah. Perhaps it gives you an idea of how a sukkah should look. Of course, a sukkah usually has four walls, or three walls built against the wall of a house.